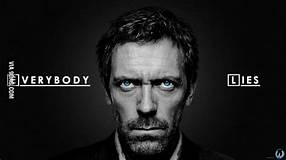

“Everybody lies.” This was the credo of the titular character in one of my all-time favorite shows: House, MD. And of course, it is true. From the saints to the malignant narcissist politicians and everyone in between, no one is completely honest all the time.

When it comes to eating disorder treatment, there is an unsettling phenomenon that is not discussed as much as it should be: the majority of eating disorder patients are dishonest about their symptoms. The dishonesty can range from occasionally telling their parents that they ate lunch while out with friends when they did not, to a minimization of symptoms, such as reporting to their therapist that they binged and purged twice in the past week when really it was six times, to a long-term deception, such as throwing away snacks for weeks or months on end while claiming to have eaten them, or performing hours of secret calisthenics in a locked bathroom or closet. With restrictive eating disorders such as Anorexia Nervosa (AN) or Avoidant-Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID), the deception often takes the form of manipulating the number on the scale by water loading right before weigh-ins or hiding heavy objects in their undergarments.

Dishonesty about symptoms is absolutely the rule, not the exception, for all eating patients ranging from innocent elementary school children who know nothing about eating disorders to the most seasoned treatment veterans who have been ill for decades and have experienced multiple stints in hospitals and treatment centers. Individuals with AN, in particular, are often very well-behaved, perfectionistic, rule-abiding individuals who have never misbehaved, and never been in trouble. Many of these kids are extremely honest with a strong moral compass; that is, until AN swept into their lives and took over their psyche.

Why is this deception so pervasive in eating disorder treatment, and what can we do about it?

First, it is important to understand why the patient is being dishonest. Eating disorder patients may be deceptive for any number of reasons. The most common reasons include:

- Extreme fear of eating and/or weight gain.

- Desire to please or appease their parents or treatment providers.

- Fear of the negative consequences of telling the truth about symptoms or revealing their true weight, which may include losing independence, being hospitalized, entering a higher level of care, having to withdraw from sports or take a leave of absence from college.

- Extreme shame or embarrassment about engaging in the symptoms (this is especially true for people who struggle with binge eating and / or purging symptoms).

- Desire to appear “better” so that they can end treatment before they are truly ready.

- Distorted perception of their eating or exercise behaviors (people with AN and ARFID tend to overestimate the amount of food that they eat and the caloric content of their food, so they may report that they are eating enough to maintain weight when in reality they are not).

- Distorted perception of what is “normal” or “healthy,” either due to the eating disorder or due to environment (for example, a 14-year-old soccer player rising at 5:00 AM to run 5 miles each morning and failing to mention this habit to the treatment team because his parents and older siblings do the same).

I recommend that treatment providers, parents, and loved ones of eating disorder patients take the following steps to address dishonesty:

Recognize the deception for what it is: a symptom of the eating disorder.

The patient is not lying because they are manipulative or immoral; they are lying because they have a severe mental illness that makes them absolutely terrified to do exactly what it is that they need to do to recover.

Deception in an eating disorder is no different than a seizure in epilepsy or low blood sugar in diabetes. It is par for the course of the illness and it is not the patient’s fault. I do not mean this in a fatalistic way. Eating disorder patients can develop the skills to be honest in recovery just as diabetics can utilize medications and dietary changes to control blood sugar.

Meet the patient with nonjudgment, empathy, and compassion.

When deception is discovered, remain calm and gentle. If the patient “came clean” and admitted to having lied in the past, commend him for his honesty now. Make it abundantly clear that you are not angry or disappointed (even if you secretly feel angry or disappointed inside). Rather, you are grateful that he has revealed this information because now you have important data to help support him more fully in his recovery. Let the patient know that you understand the deception as part of his eating disorder, not a reflection on his true character.

Explore the emotions that have arisen for the patient surrounding the deception and surrounding the disclosure of deception.

Did he feel guilty for lying over a period of time? Was she experiencing extreme inner conflict between the compulsion to engage in an eating disorder behavior vs. a drive to follow the treatment recommendations? Is he feeling ashamed, or relieved, now that the secret is out in the open? Helping the patient explore these thoughts and feelings around the deception helps him feel heard and validated and also opens the door for a deeper connection.

Initiate a dialogue with the patient to help discover what is motivating the eating disorder behaviors.

Why is the patient throwing away her lunches? Does she dislike the food? Are her friends all dieting? Is she studying during lunchtime instead of eating? Is she too full after a large breakfast and morning snack? Is she afraid of gaining weight? Is she embarrassed to eat “so much” in front of her peers? There may be multiple motivations behind the behavior. Some of the motivations may be disordered (e.g., a strong desire to lose weight) and some may be perfectly normal (e.g., not liking the taste of the food or not being hungry). Regardless of the motivation(s) behind the eating disordered behaviors, the behaviors must stop. To someone with an eating disorder, skipping lunch because “school food sucks” is just as dangerous as skipping lunch due to drive for thinness.

Ascertain the reason(s) for the deception.

Many eating disorder patients have very good reason for being deceptive, and their reasons should be understood and respected (though not necessarily condoned). This is analogous, in a sense, to the reality that most LGBTQIA individuals were “in the closet” until this century, and many are still in the closet today. Being honest about their sexuality or gender identity would have led to discrimination, ridicule, oppression, disownment, or worse. Pretending to be straight or cisgender was an act of self-protection, born of realistic fear.

Whether you are the parent, the therapist, the dietitian, or the boyfriend, ask the patient whether there is something about you, or something about your relationship with them, that drives them to be dishonest. For example, many patients are very attuned to their parents’ anxiety, and the parents’ anxiety feeds into the child’s anxiety. Patients may hide or minimize their symptoms to control their parents’ anxiety as a roundabout way to manage their own anxiety. Some treatment providers or parents may outwardly express disappointment in the patient or anger towards him when he has lost weight or struggled with eating disorder symptoms. Whether you are a parent or a treatment provider, it is natural to feel angry, disappointed, or terrified when your child or patient is struggling with symptoms. However, expressing these emotions directly to the patient is rarely helpful and may even make the situation worse.

Use this conversation to help build trust and resilience and to create an environment more conducive to recovery and honesty.

If the patient is minimizing symptoms due to shame or embarrassment, talk about it! The best way to unpack and dismantle shame is to bring it out into the open. Try to understand why the patient is feeling ashamed (perhaps because the eating disorder is compelling him to act in ways that are incongruent with his personal values and goals), and help him begin to let go of the shame. Let him know that there is no shame in being authentic about struggles and seeking help.

If the patient is dishonest about symptoms due to fear of making their parents anxious, angry, or disappointed, then part of the parents’ work is to learn to manage their own emotions around their child’s symptoms. Therapists are trained to do this. Parents are not, and it is much harder for parents to be neutral or objective about their own children, especially when their children are unwell. This is one of many reasons why therapists are not supposed to treat their own children! Parents can have conversations with their children about how they can best respond to their child’s symptoms in a way that promotes honesty.

Change the environment to make it very difficult, if not impossible, for the dishonesty to persist.

Leaving a patient to struggle with the eating disorder without adequate support is cruel and sets everyone up for failure and disappointment. If the patient has been skipping lunches or snacks, it is best to arrange support and supervision around lunch and snacks for a sustained period of time – usually weeks or months – until the patient is well enough to eat on her own. If the patient has been secretly binge eating in the evenings, arrange some support around that vulnerable time period, such as watching a family movie together or going for a walk. If the patient has been hiding heavy objects in his clothing for weigh-ins, consider doing future weigh-ins with minimal clothing, or on random days, to make it harder for the patient to prepare.

Frame the dishonesty, the disclosure, and the subsequent collaborative problem-solving as a stepping stone towards a stronger recovery and a more trusting relationship.

Everyone makes mistakes and experiences setbacks. This is a natural and inevitable part of recovery. These experiences, if handled skillfully, can help the patient build a stronger foundation for full and lasting recovery and help build a deeper trust in their support system to keep them safe and healthy.

Is this also true for other hidden and deceitful behaviors that the patient w and ED has? Behaviors that are not directly related to eating, but are hidden or lied about and may be due to shame, fear, or a sense of control over a situation? Is this also a symptom of anorexia?

It is not uncommon for patients with eating disorders to have other deceitful behaviors that are not related to food, weight, or exercise. If the deceit is not directly related to eating disorder symptoms, then I would not consider the deceit a symptom of anorexia. However, the deceit could certainly be related to shame, fear, confusion, or other challenging emotions. I would recommend the same approach to the deceit whether it is a symptom of anorexia or not. The bottom line is that the patient is suffering; their dishonesty is likely born of suffering, and they deserve to be met with compassion, understanding, and support rather than judgment or punishment.